This is an old revision of the document!

Introduction to ECS

OOP Quirks & Limitations

Prior to discussing some ECS concepts, we have address the object-oriented programming (OOP) and its issues, since the current state of Unreal Engine’s user-level API is basically OOP-based. The actor’s component model is also kind of limited and is mostly static in nature.

While developing games (and software in general) OOP-way, we decompose of all the available entities and concepts into hierarchies of their corresponding types. In terms of Unreal Engine those are mainly called Objects, or ''UObjects'' if we are talking about C++ coding, so we create hierarchies of types (classes) derived from a single root UObject ancestor. Every time we create a new Blueprint (or a C++ class) it basically derives from this root class.

As the time goes we notice that our classes become more and more in common and begin to refactor the codebase (or the Blueprint assets), while extracting those common facilities into some separate base classes. Those in turn become the ancestors and we derive certain types from them, that should share their functionality.

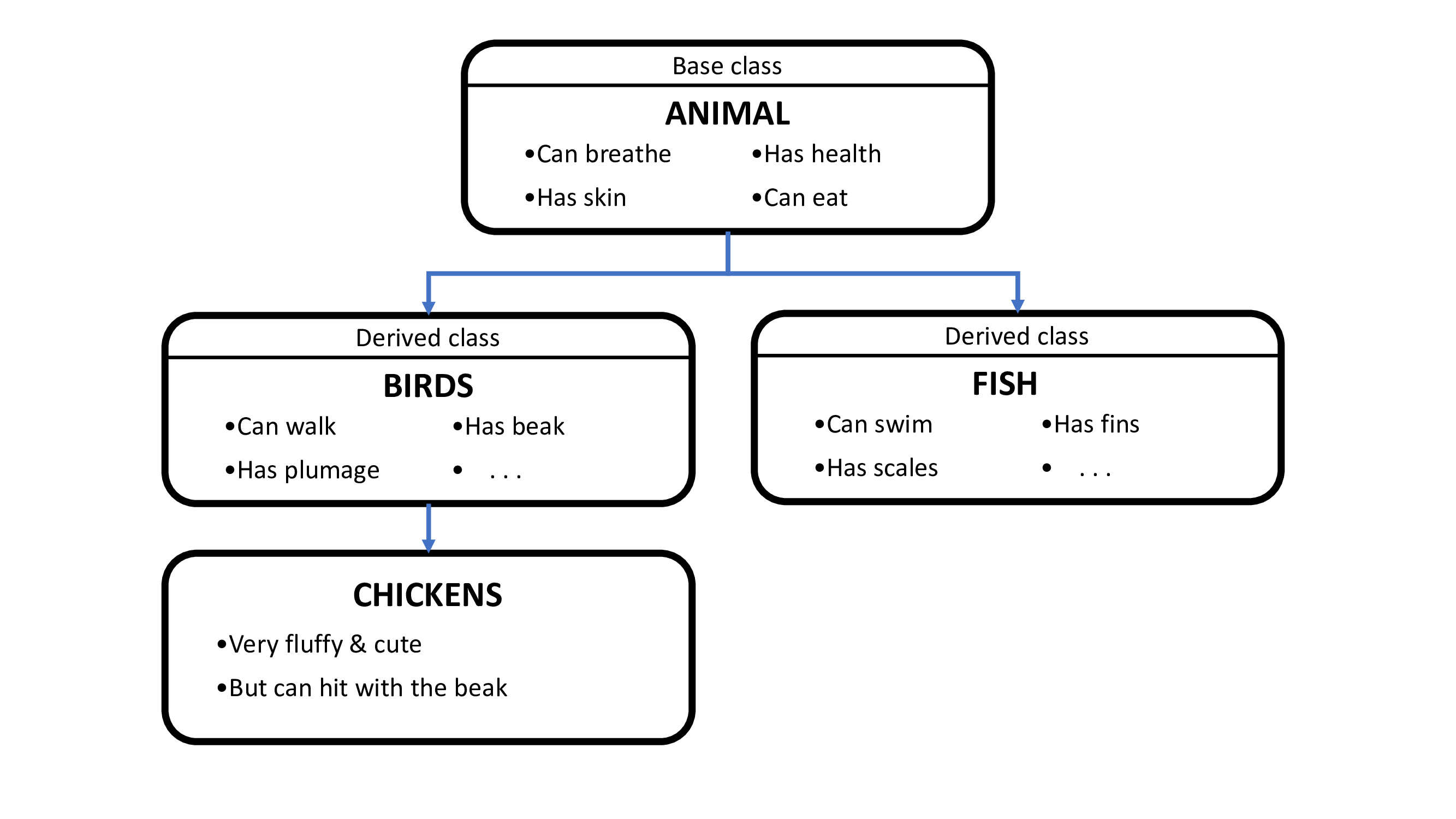

A quite popular example for that approach is a tree of animal inheritance, where a root class represents basically any animal existing (something like UObject), while others derived represent some separate animal sorts and kinds on their own:

The descendant types inherit the properties of their respective base types, so by altering the base class properties we also change the current state of the objects, if they are of some derived descendant type. We can also introduce some "virtual" overridable methods to be able to modify their behavior in the derived classes.

All of that functionality surely look quite useful and nice, isn’t it? Well yes it is, until you have like 100 classes. The problem here is that your game logic becomes too scattered across the class-layers in the hierarchy. You tend to forget what is defined on what level, what is overridable and what’s not. The amount of coupling between the entities becomes scary and error-prone. Your coding partners who wrote some aspect of the base classes, become the keepers of some “secret knowledge”. The time of refactoring sky-rockets for this every-growing hierarchy. This “ceremonial” job becomes your job itself, but not the development of the final end-user features. Not a good thing at all, considering how limited the time and resources can be.

ECS to The Rescues

A solution to this hassle could be an approach called Entity–component–system (or ECS for short).

There are no hierarchies in terms of ECS, as every game object (i.e. entity) is basically flat in its nature. It consists of data-only parts called components. You can combine those arbitrary on a per-entity basis.

Want your RPG character become a poison damage dealer? Add a poisonous component to it and consider it done, as long as you also implement a system that actually solves the poison mechanic.

Systems are remote to the details they operate upon. That’s also a feature of ECS. They are like distant code blocks that take certain details as their operands and evaluate a certain result. Systems are run after other systems and together they form a complete pipeline of your game.

That’s basically it. But how come such a useful concept is not implemented in Unreal Engine yet? Well, it actually is, take Niagara as an example. The rendering pipeline can also be considered a pipeline. In other words, that may be all sorts of specific data-driven approaches taken in Unreal Engine, but none of them are as general-purpose as its OOP nature. We provide such approach for any of the user-available side of the Engine!

Make sure your read our Apparatus to ECS Glossary to get to know our terminology.

About ECS+

Apparatus takes a broader approach on ECS that we essentially call ECS+ over here. It introduces a greater amount of flexibility with the help of detail (component) inheritance support and sparse expandable, dynamic belts (chunks and archetypes), subject (entity) booting, etc. The term ECS+ in itself should be treated as more of a synonym for the “Apparatus” wording itself, since the product actually implements it and uses a different terminology from the ground up.

Generally speaking, in our own development philosophy, engineering should never be “pure” or “mathematically correct” but mainly applicable and useful to the end user and/or the developer. Unreal Engine in itself is actually a good demonstration of this approach with so many special cases and design patterns. By having both OOP and ECS patterns combined Apparatus takes the best of three worlds, with UE‘s blueprint world counted.

Built-in Subjects

At a lower level, Subjective is an interface and any class that implements it may be called a Subject. There are several subjects already implemented in the framework:

SubjectiveActorComponent(based onActorComponent),SubjectiveUserWidget(based onUserWidget),SubjectiveActor(based onActor).

Those should be sufficient for the most cases, but you can easily implement your own additional subject classes in C++.

Built-in Mechanisms

The Mechanical class is also an interface, with the most useful mechanisms already implemented:

MechanicalActor(inherited fromActor),MechanicalGameModeBase(GameModeBase),MechanicalGameMode(GameMode).

You would hardly ever need to implement your own mechanisms. Should you wish to, you can also do it in C++.